Contemporary investigative practices. The challenges of his new epistemological approaches

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.29394/Scientific.issn.2542-2987.2018.3.7.0.6-15Keywords:

publishers, research, scientific developmentAbstract

The scientific and technical development in contemporaneity configures a new investigative thought. From this perspective, quantitative approaches are accompanied by phenomenological understandings for the explanation of processes. While qualitative research involves resources and quantitative measurement and explanation techniques.

One of the problems that researchers face when organizing an investigative process is to select a methodology that is relevant to the nature of the object / subject of study. This selection leads them to take sides in favor of processes of a quantitative or qualitative nature, with plural points of view depending on the ways of perceiving and understanding the panorama before them. In addition, the conformation of a scaffolding of methods and techniques of positivist or phenomenological cut or where a complementarity between both must be expressed.

We have an example in the study of human behavior where we can not lose sight of the causal nature that originates human behavior and the peculiar combination of heredity and the environment, the reasons and the orientation towards conscious goals and objectives. In this study, the use of quantitative methods and techniques may be relevant, as well as those that explore human subjectivity.

The epistemological debate between rationalist and empiricist paradigms lacks a sufficient basis, since particular methods are not necessarily linked to a paradigm.

The so-called positivist paradigm (quantitative, empirical-analytical, rationalist) seeks to explain, predict, control phenomena, verify theories and laws to regulate phenomena; identify real, temporally preceding or simultaneous causes.

On the other hand, hermeneutic rationality (qualitative, phenomenological, naturalistic, humanistic or ethnographic) seeks a way to approach, study, understand, analyze and build knowledge; from processes of interpretation where the validity and reliability of knowledge rests, ultimately, on the rigor of the researcher. The construction of knowledge is assumed as a subjective and intersubjective process. In the meantime, it is the subject who constructs the research design, collects the information, organizes it and gives it meaning from its previous conceptual structures; as well as the findings that arise from the research itself, which are then collectivized and discussed in the academic community.

Erlandson, Harris, Skipper and Allen (1993), contrast traditional (quantitative) design with emergent design (typical of the inquiry derived from the naturalist paradigm). The difference between the two lies in the specificity of the original research plan.

If qualitative research seeks to understand meanings; quantitative studies try to know little explored issues through the effectiveness of techniques.

Stake (1999: 41), noted:

“This distinction between quantitative and qualitative methods is a matter of emphasis - since reality is the mixture of one and the other. In any ethnographic, naturalistic, hermeneutical or holistic study (eg, in any qualitative study) the enumeration and recognition of the difference in quantity occupy a prominent place. And in any statistical study or controlled experiment (eg, in any quantitative study) the natural language with which they are described and the interpretation of the researched are important”.

For Hashimoto and Saavedra (2014: 8), “The discussion has to focus on why I should or have to use that or another method, or in what I should look for or use that data or method”. That is the crux of the matter, to resolve this question is on the philosophical and not methodological level.

Guba and Lincoln (2002: 113), state:

“From our perspective, the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods may be appropriate for any research paradigm. In fact, questions of method are secondary to those of paradigm, which we define as the basic belief system or worldview that guides the researcher and not only to choose the methods, but in ways that are ontological and epistemologically fundamental”.

The theme of methodological complementarity goes through the dilemma of the absence of basic epistemological foundation to approach reality. McMillan and Schumacher (2005: 128-129), point out that quantitative research is based on some form of logical positivism that seeks to establish how things are by avoiding value judgments; while qualitative research is based on constructionism, which seeks to explain how people come to describe, explain or give an account of the world where they live. These two traditions are often seen as antagonistic and without possibilities for discussion or cooperation.

The proposal of complementarity between the two paradigms can be considered as a valid option in research; because each one of the methodologies makes important contributions to the construction of knowledge. Its rigid use, without doubts, impoverishes the process of searching for new knowledge, by preventing the incorporation into the investigative process of the benefits that each of them possesses and prevents reaching more interesting findings.

The possibilities of complementation can be based on the principles of consistency and dialectical unity. The quantitative in its hypothetico-deductive logic contributes to the process the explanation and the relation of cause and effect. In turn, the qualitative with its inductive-deductive understanding goes into the complex paths of construction and decoding of meanings of human subjectivity, which considers the individual and the group, as a result of the social processes that each one lives. Therefore, complementarity allows us to take advantage of the strengths of one method to compensate for the weaknesses of the other.

Taking into consideration Serrano, Blanco, Ligero, Alvira, Escobar and Sáenz (2009: 16-17), “... the combined use of both perspectives within the same investigation has become a commonly accepted place and It has even reached a point where we can talk about the “social desirability” of multi-method research”.

The thematic focuses of this volume of the Revista Scientific. they clearly show its different sections, among them: the transformation of teaching practices; innovative experiences to improve the educational and teaching-learning processes within the classroom framework; virtual learning environments, information and communication technologies and the one related to environmental education. Towards there lead the questions that cross the diverse articles as testimony of the scientific results that each author proposes.

In their epistemological approaches, a journey through different methodologies, methods and techniques is appreciated. It is traveled from quantitative, qualitative or methodological completions; respecting, as previously mentioned, the nature of the object of the research carried out.

Finally, the importance of the themes of this issue of the Journal lies in the reflection on the different edges of the formative processes, in various contexts and levels of teaching. It also resides in the look at the logics in use, committed to different methodologies; which must be judged according to the success achieved in the investigations.

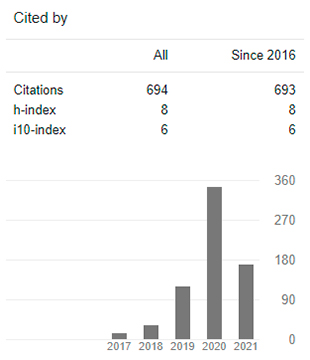

Downloads

References

Erlandson, D., Harris, E., Skipper, B., & Allen, S. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry: a guide to methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Guba, E., & Lincoln, Y. (2002). Paradigmas en competencia en la investigación cualitativa. En: Denman, C. y J.A. Haro (comps.). Por los rincones. Antología de métodos cualitativos en la investigación social. Hermosillo, Sonora, México: El colegio de Sonora.

Hashimoto, E., & Saavedra, S. (2014). La complementariedad paradigmática: un nuevo enfoque para investigar. Congreso Iberoamericano de Ciencia, Tecnología, Innovación y Educación. Buenos Aires, Argentina: OEI. ISBN: 978-84-7666-210-6, págs. 21. Recuperado de: http://www.oei.es/historico/congreso2014/memoriactei/399.pdf

McMillan, J. & Schumacher, S. (2005). Investigación Educativa. Una introducción conceptual. Madrid: Pearson Addison Wesley, 5th Edición, págs. 656. Recuperado de: https://revistas.uam.es/tarbiya/article/viewFile/7222/7583

Serrano, A., Blanco, F., Ligero, J., Alvira, F., Escobar, M., & Sáenz, A. (eds.) (2009). La investigación multimétodo. Madrid, España: Universidad Complutense Madrid, págs. 94. Recuperado de: http://eprints.ucm.es

Stake R. (1999). Investigación con estudio de casos. Segunda edición. Madrid: Ediciones Morata. ISBN: 84-7112-422-X, págs. 155. Recuperado de: https://www.uv.mx/rmipe/files/2017/02/Investigacion-con-estudios-de-caso.pdf

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2018 INDTEC, C.A.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The content of the journals of this site, are under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 International License.